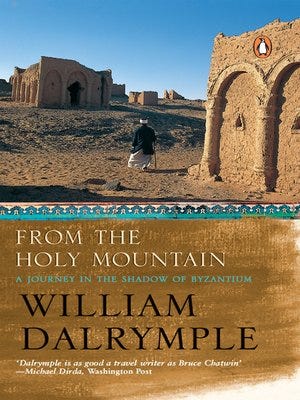

William Dalrymple

From the Holy Mountain: A Journey among the Christians of the Middle East

New York: Random House, 1997.

William Dalrymple is a Scottish historian of South Asia and the Middle East. He is known for bestselling books such as The Anarchy (about the East India Company) and The Return of a King (about the British invasion of Afghanistan in the nineteenth century). This book, From the Holy Mountain, is now 25 years old, but it is a great read about Christian communities from Mount Athos in Greece all the way around to the remote town of Asyut in the Egyptian desert.

Dalrymple follows in the footsteps John Moschos, the spiritual monk who visited the many monasteries of the Byzantine world on the eve of the Arab conquests and detailed his journeys in his book The Spiritual Meadow. The book is a travel diary of the holy, the harrowing, and horrible things that Dalrymple encountered along the way. He dodges secret police and sectarian fanatics, listens to survivors of the Armenian genocide, dines with diplomats, sings Gregorian chants in Aleppo, takes tea with warlords, converses with monks about Free Masons and chicken-farming, beholds famous relics, walks through the ruins of abandoned churches, reads rare books, and sleeps in fortified monasteries.

Dalrymple has written a book that reads like a digest of Voice of the Martyrs as he provides accounts, historical and present (1990s “present”), of Christian persecution in the Middle East. He explains theological controversies related to Monophysites and Nestorians, Dalrymple mixes with the Greek Orthodox of Greece, Armenian and Syrian Orthodox in Turkey and Syria, Maronites in Lebanon, Palestinian Christians in Israel, and Coptic Christians in Egypt.

Many years ago, I read Philip Jenkins's The Lost History of Christianity, which is about the history of the churches in Africa, India, and Asia. I felt like Dalrymple’s book is a natural sequel to Jenkins’s as it tells us much about the history of “Far Eastern” or “Oriental” churches into the twentieth century.

The book in many ways is quite prescient. Back in the late 90s Dalrymple was raising the alarm about the emptying of Christians from the Middle East due to persecution and emigration. Now, after 9/11, the Iraq War, the Afghanistan campaign, the Syrian civil war, and the Israel-Gaza conflict, things have only gotten worse.

The book is an entertaining travel diary with humour and adventure, it is also a tragedy that documents the violent persecution of Christians, it takes one into the life and times of John Moschos, it shows the last remnants of Christian monasticism in the Middle East, which makes for a lively and informative read.

There are a lot of interesting tidbits about things like how the Hugeonots found the Ottoman Empire more tolerant than Catholic Europe. There were once Nestorian universities in Nisbis (Iraq), Jundishapur (Iran), and Merv (Uzbekistan). The melting pot of religions and sects in ancient Edessa. The persecution of Suriani (Syrian Christians) by Turks and Kurds. The Yezidis as a Gnostic offshoot of the Nestorian church.

Some great quotes too:

“Such are the humiliations of the travel writer in the late twentieth century: go to the ends of the earth to search for the most exotic heretics in the world, and you find they have cornered the kebab business at the end of your street in London.”

While Dalrymple reports how Christians in Syria felt safe compared to those in Turkey, Lebanon, and Israel, yet he pointed out: “The only problem with all of this, as far as the Christians are concerned, is the creeping realisation that they are likely to expect another, perhaps far more savage, backlash when Assad dies or when his regime eventually crumbles. The Christians of Syria have watched with concern the Islamic movements which are gaining strength all over the Middle East, and the richer Christians have all invested in two passports (or so the gossip goes), just in case Syria turns nasty at some stage in the future.” Wow, those intuitions were proved right by the Syrian civil war.

“Certainly if John Moschos were to come back today it is likely that he would find much more that was familiar in the practices of a modern Muslim Sufi than he would with those of, say, a contemporary American evangelical.”

“The Qanubbin Gorge [in Lebanon] was once famous for producing saints. Now it is more remarkable for the number of Christian warlords and mafiosi that spring from its soil.”

Fr. Theophanes of Mar Saba monastery in Israel discoursed about hell: “It’s going to be full of Freemasons, whores and heretics: Protestants, Schismatics, Jews, Catholics … More ouzo?” On why he hated Freemasons, “Because they are the legions of the Anti-Christ. The stormtroopers of the Whore of Babylon.”

Something very relevant for today: “Few Western Christians are aware of the degree of hardship faced by their co-religionists in the Holy Land, and the West’s often uncritical support of Israel frankly baffles the Palestinian Christians who feel their position being eroded year by year.”

“You won’t believe this,” said Fr Dioscuros, “but we had some visitors from Europe two years ago - Christians, some sort of Protestants - who said they didn’t believe in the power of relics!”

Probably the most important insight is on how the diverse Christian groups of the Middle East face diverse threats and dangers.

When I began this journey I had expected that Islamic fundamentalism would prove to be the Christians’ main enemy in every country I visited. But it had turned out to be more complicated than that. In south-east Turkey, the Syrian Christians were caught in the crossfire of a civil war, a distinct ethnic group trodden underfoot in the scrummage between two rival nationalisms, one Kurdish, the other Turkish. Here it was their ethnicity as much as their religion which counted against the Christians: they were not Kurds and not Turks, therefore they did not fit in. In Lebanon, the Maronites had reaped a bitter harvest of their own sowing: their failure to compromise with the country’s Muslim majority had led to a destructive civil war that ended in a mass emigration of Christians and a proportional diminution in Maronite power. The dilemma of the Palestinian Christians was quite different again. Their problem was that, like their Muslim compatriots, they were Arabs in a Jewish state, and as such suffered as second-class citizens in their own country, regarded with a mixture of suspicion and contempt by their Israeli masters. However, unlike most of the Muslims, they were educated professionals and found it relatively easy to emigrate, which they did, en masse. Very few were now left. Only in Egypt was the Christian population unambiguously threatened by a straightforward resurgence of Islamic fundamentalism, and even there such violent fundamentalism was strictly limited to specific Cairo suburbs and a number of towns and villages in Upper Egypt, even if some degree of discrimination was evident across the country. But if the pattern of Christian suffering was more complex than I could possibly have guessed at the beginning of this journey, it was also more desperate. In Turkey and Palestine, the extinction of the descendants of John Moschos’s Byzantine Christians seemed imminent; at current emigration rates, it was unlikely that either community would still be in existence in twenty years. In Lebanon and Egypt, the sheer number of Christians endured a longer presence, albeit with ever-decreasing influence. Only in Syria had I seen the Chrisitan population looking happy and confident, and even their future looked decided uncertain, with most expecting a major backlash as soon as Asad’s repressive minority regime began to crumble.

In sum, a fascinating read for anyone interested in the story and plight of Christians in the Middle East. It has to be acknowledged that the situation has changed massively since the late 90s when Dalrymple wrote, but the book shows how deeply in-grained Christianity is in the history and culture of the Middle East, and it gave what seem to be now prophetic warnings about how vulnerable Christians in the Middle East are to sectarian violence and state-backed persecution.

I read Dalrymple about 20 years ago and was ashamed at the paucity of my knowledge. Mandeans who accept only the baptism of John the Baptist were an offshoot totally unknown to me and my church. In some areas of Sussex there is another influx of refugee Christians, and there increasing numbers of Coptic Christians, and Iranians who worship in their native Farsi. I wonder if there may be another migration of Palestinian Christians and how we would cope, considering that Govt seem to accept uncritically the Israeli stance in the conflict. Having heard from "the pulpit" (we don't have one its the inerrancy position of who is speaking!) "Israel is God's chosen people and so whatever they do we must support them" I'm at my wits end! Read your bible intelligently and read Dalrymple, pray for wisdom and peace!

Also thanks for book review very interesting to learn more about the Christian church in Middle East history